A memento of the importance of the port of Le Havre for German emigration to the United States is John Shea's Englisch-Amerikanisches Handbuch für Auswanderer und Reisende, which was published in Le Havre in 1854. It claimed to be "the first book of the kind ever attempted in Havre for the instruction of the English language to emigrants", with a phrase book and a pronunciation guide. Besides reprinting the regulations for steerage passengers to New York and New Orleans in both English and German, it also provided a list of emigration agents, noting "By their endeavors, Havre has become the thoroughfare of emigration from Switzerland and the South of Germany to the United States..." This now obscure work was an attempt to cash in at the high point of the first boom period for emigration via Le Havre, which would taper off at the end of the decade.

To some extent, Le Havre owed its existence to America, since its harbor was constructed by Francois the First in 1519 for colonial expeditions. Its function as an emigration port took on a new quality after the end of the Napoleonic wars, when mass movement once again became possible. Secondly the developing cotton industry in Alsace required raw material from the United States. German disunity, and the resulting multiple tariffs imposed on Rhine river traffic made it cheaper to do this overland, across France. As elsewhere, the shipment of persons was a by-product of commercial shipments: the docks at Le Havre were enlarged and steamboat traffic on the Seine increased. Emigrants could obtain transport on freight wagons returning from the east. They were at first mainly Swiss and Alsatians. At any rate, according to a letter from Le Havre sent to the prefect of the department of the Moselle on May 20, 1841, "Here, no distinction is made between German and Alsatian emigrants, they are all just called Swiss." (quoted in Camille Maire, L'émigration des Lorrains en Amérique 1815-1870, Metz 1980). Due to the timber trade, a certain number of Norwegians sailed to Le Havre and then boarded ships to America.

As a result, traffic between New Orleans and Le Havre was particularly important, although New York was also involved in the trade in cotton and was of course a magnet for immigrants. The majority of immigrants did not remain in Louisiana, but proceeded up the Mississippi to St. Louis and Cincinatti, at least before the expansion of the U.S. railway system. In 1818, passage from Le Havre to America was 350-400 francs; in the early 1830s it was 120-150 francs. Leaving aside the difficult question of how much this was "worth" in purchasing power, the fact remains that the increase in shipping (including regual packet service) had left to a dramatic decrease in prices for transport. The majority of these ships were American. Since the only emigration lists that have survived are for French ships, this leaves an enormous gap in the records.

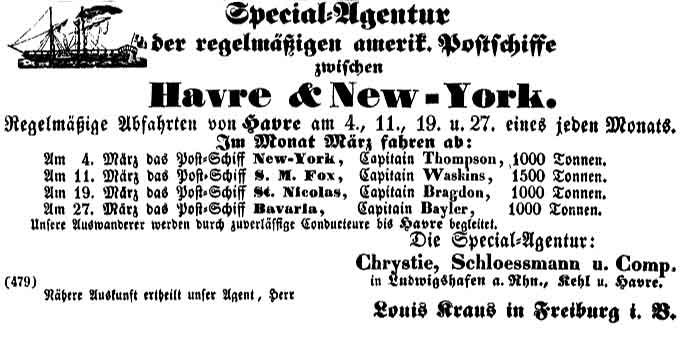

At first, it was necessary for emgirants to make arrangements for passage directly with the captains. During the sailing season there were thus always several thousand persons waiting to leave. They could be obliged to wait for weeks, partly in lodging houses, partly outdoors. A German colony of innkeepers, shopkeepers and brokers appeared to service them. Agents began meeting the emigrants on the road to Le Havre to sign them up. After the French government required in 1837 that Germans present a valid ticket at the French border, local offices began to be opened in Switzerland and the German states. Again, as elsewhere, French authorities did not want large numbers of indigent would-be emigrants stranded in the port. Previously, the only document required to cross the border had been a passport. The mechanisms of recruitment, transport across France and lodging will be treated separately in the future.

There is some difference of opinion as to why the nmber of emigrants who went through Le Havre began to decline. In 1854, it is true, the Prussian government forbade its subjects to emigrate via France, but this ban was lifted in May 1855. Despite growing competition, mainly from Bremen, Le Havre could still have held its own. An economic slump in the USA slowed immigration in 1858, but this applied equally to all European ports. The development of the French railway system also made passage across France easier (one day's travel from the border to Paris). Yet, although the state railway system offered reduced fares and even special trains in the spring, it seems that in general the French railroads were more expensive than German ones. A ticket from Mayence (Mainz) to Le Havre in the 1850s cost 40.65 francs, to Antwerp only 12 and to Bremen 15.50 (Camille Maire, En route pour l'Amérique, Nancy 1993). Jean Braunstein suggests that there were stricter border controls in 1858, due to an attempted political assassination, which was then exaggerated by the German press.

During most of this period, emigrants were required to bring their own provisions. It is sometimes that this was disadvantage compared to German ports, where early on, emigrants were provided with meals on board. In reality, many southern Germans were decidedly unimpressed by North German cuisine and such unfamiliar foods as herring, and preferred to bring their own. On the other hand, Bremen and Hamburg did take more steps to protect emigrants from unscrupulous agents and salesmen who sold them overly expensive and sometimes unncessary goods.

In figures:

| Year(s) | Germans | Total | % | Remarks |

| 1830 | 400 to 450,000 Germans embarked during the years 1830-1847 | |||

| 1837 | 5,527 | 8,311 | 66.5 | |

| 1838 | 2,677 | 4,122 | 65 | |

| 1839 | 7,800 | 10,110 | 77 | |

| 1844 | 19,600 | |||

| 1847 | 40,000 | |||

| 1848 | 25,506 | |||

| 1849 | 33,898 | |||

| 1850 | 25,824 | |||

| 1851 | 44,234 | |||

| 1852 | 45,806 | 72,325 | 63 | |

| 1853 | 54,000 | 68,836 | 78.5 | from 1855 to 1862 80,000 Germans embarked in Le Havre |

| 1856 | 13,317 | 22,873 | 58.2 | |

| 1857 | 18,425 | 38,700 | 47 | |

| 1858 | 8,300 | 18,235 | 45.5 | |

| 1859 | 6,500 | 15,393 | 44.5 |

Regional compositon of emigration

In a list from 1840, of 81 persons, 30 came from the Bavarian Rhinleand, i.e. the Palatinate, rather than Bavaria proper, 41 came from the Prussian province of the Rhineland and 4 from Baden. In 1848, of 725 Germans, 535 were from the Palatinate, 186 from the Prussian Rhineland, 28 from Baden, 16 from Hessen-Darmstadt and 7 from Württemberg. In 1852 the breakdown was:

| Bavaria | 22,411 | 49% |

| Baden | 16,021 | 35% |

| Hessen | 3,689 | 8% |

| Prussia | 3,685 | 8% |

For the period up to 1860 there has been little historical research done in English on Le Havre as an emigration port since Marcus Lee Hansen's classic The Atlantic Migration 1607-1860 (first published in 1940, after his death, and re-edited in 1961), and none at all in German as far as I can tell. In French, the main study is Camille Maire, En route pour l'Amérique. L'odyssée des émigrants en France au XIXe siècle (Nancy 1993) supplemented by her L'émigration des Lorrains en Amérique 1815-1870 (Metz, 1980). A further source is Jean Braunstein, "L'émigration allemande par le port du Havre au XIXe siècle", Annales de Normandie, Vol. 34, no.1, mars 1984.

The genealogical association "Groupement Généalogique du Havre et de Seine Maritime" http://gghsm.free.fr/index.htm

has passenger names from 1780-1835. Their web site also has a few names of German Catholics who were married at the "German Chapel" in Le Havre in the 1860s: http://gghsm.free.fr/Chapelle.htm . (In French only)